Bangladesh's Interim Government: A Crisis of Justice in the Name of Democracy

After Sheikh Hasina was ousted from power in 2024, the interim government led by Dr. Yunus promised democracy. But in reality, it has brought judicial control, suppression of opposition, persecution of journalists, and the resurgence of extremism. Bangladesh is now in a political crisis devoid of justice.

Bangladesh's Interim Government: A Crisis of Justice in the Name of Democracy

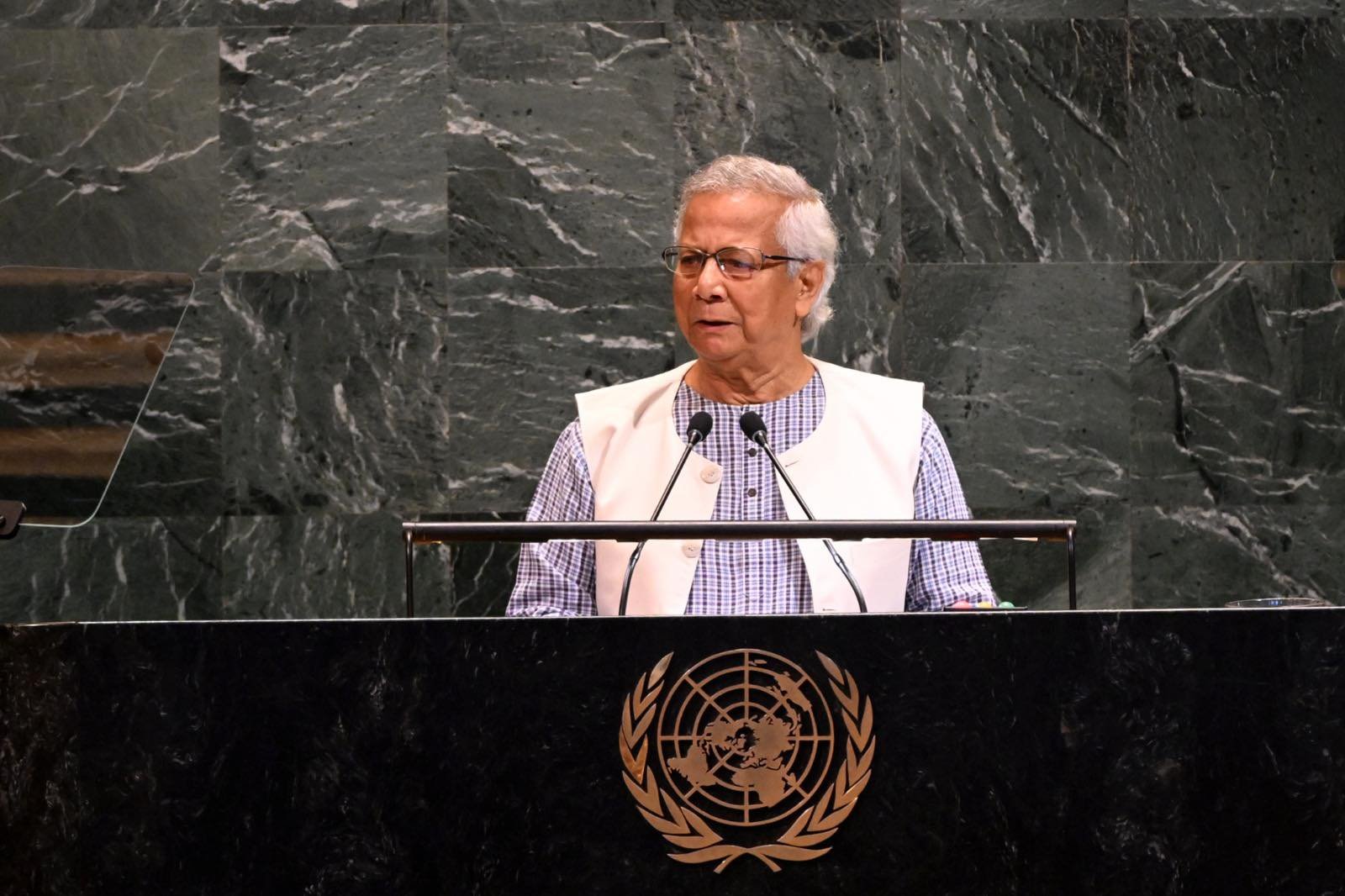

DHAKA — In the aftermath of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was ousted from power in 2024, Bangladesh stood at a historic crossroads. Millions had poured into the streets demanding change. When Nobel laureate Dr. Muhammad Yunus took charge of the interim government on August 8, hope briefly surged. But within months, observers say the country slid into an equally sinister pattern: a legal and institutional breakdown where the promise of democratic renewal has been replaced by judicial repression, emboldened extremism, and selective rule of law.

Weaponizing the Courts: From Reform to

Reprisal

What began as a vow

to deliver accountability quickly morphed into what many rights groups now

describe as a politically charged purge. By May 2025, over 266

journalists were facing criminal charges—many under the Digital Security

Act (DSA) and Cyber Security Act (CSA)—for covering or criticizing

the government’s handling of protests and dissenting voices.

The Awami League

(AL), once the ruling party, was officially banned on May 10, 2025

under Bangladesh’s Anti-Terrorism Act—a move condemned by the UN

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights for "undermining a

return to a genuine multi-party democracy."

Simultaneously,

courts have fast-tracked charges against former ministers and AL leaders for

“crimes against humanity,” while Dr. Yunus himself had a six-month

conviction overturned quietly by the High Court just one day before taking

office.

Awami League’s

perspective was echoed anonymously, who told us:

“This is not

justice—this is political revenge in legal disguise. The interim government has

hijacked the judiciary to do what it cannot justify democratically. These laws

were never meant to silence political opposition, yet that’s all they’re doing

today.”

Legal experts also

argue this is not justice, but a breach of fundamental judicial norms.

One senior advocate of the Supreme Court, speaking on condition of anonymity,

explained:

“The selective use

of laws like the Anti-Terrorism Act 2009 and Digital Security Act

violates both Article 27 (equality before law) and Article 35 (right

to fair trial) of the Constitution. What we are seeing now is a judiciary

being wielded as a political weapon.”

Further troubling

was the mass resignation of Chief Justice Obaidul Hassan and five senior

judges on August 10, following public pressure from student leaders aligned

with the new regime. While framed as a "reorganization," it has

effectively installed executive-friendly justices and left the judiciary

vulnerable to political influence.

Empowering the Extremists: Jamaat’s

Return and a Dangerous Gamble

One of the most

alarming reversals came on August 28, 2024, when the Yunus government lifted

the anti-terror ban on Jamaat-e-Islami, Bangladesh’s largest Islamist

party, previously outlawed for links to extremism and war crimes.

In the days that

followed, Mufti Jasimuddin Rahmani, chief of the banned al-Qaeda–linked Ansarullah

Bangla Team, was released, alongside Brig. Gen. Abdullahil Azmi and Ahmad

Bin Quasem, both suspected of ties to Pakistan’s ISI and Jamaat’s militant

wing.

Since their release,

these individuals have publicly rallied against secularism and demanded

the continued ban on the Awami League. According to Netra News, Rahmani’s

rallies directly preceded the government’s decision to outlaw AL, suggesting government

capitulation to Islamist pressure.

The return of

extremist voices has also sparked renewed attacks on minorities. In

Cumilla, Hindu temples were vandalized, while Ahmadi and Buddhist

communities faced harassment—echoes of the sectarian violence once

suppressed under prior regimes.

Legislation as a Tool of Oppression

Rather than

dismantle the authoritarian laws of its predecessor, the interim regime has expanded

them. It introduced amendments to the International Crimes (Tribunals)

Act, 1973, allowing tribunals to ban political organizations, a move

HRW warns could violate international standards of due process and freedom

of association.

The Enforced

Disappearances Law, another bill pushed by the new administration, excludes

past or systematic disappearances—letting those responsible for previous

atrocities escape accountability. HRW criticized the bill as “a whitewash” that

fails to meet international legal standards.

These legislative

moves represent what HRW called a “structural reconfiguration of

authoritarianism under democratic disguise.” Constitutional guarantees like

freedom of association (Art. 38) and freedom of speech (Art. 39)

are now routinely sidelined.

The International Community

Watches—But Acts Little

Initially, the U.S.,

U.K., and EU welcomed Dr. Yunus’s appointment, hoping for stability and

reform. However, as repression escalated, so did global concern. A joint

statement from Amnesty International, CPJ, and Human Rights Watch in March

2025 urged the government to “guarantee the right to free expression” and cease

attacks on journalists.

Still, no sanctions

followed. The UNHRC’s February 2025 report condemned the judicial overreach

and minority attacks, but implementation has stalled. India,

notably, has stayed silent—choosing strategic proximity over democratic

principle.

Manipulating the Global Narrative

The interim

government has also struggled to contain international scrutiny. When The

New York Times published an exposé warning of rising Islamist influence, it

drew immediate rebuke from the administration. Government advisers claimed

there was “no rise in militancy,” even as extremists marched freely in Dhaka.

A counter-editorial

in The Business Standard admitted that mere rebuttals are failing,

and warned the government must “proactively manage its international image with

transparency, not censorship.”

Conclusion: A Judiciary in Ruins, a

Democracy in Retreat

The evidence is

stark: Bangladesh’s interim government has betrayed its promise of

democratic renewal. Its justice system, far from independent, has been converted

into a weapon—one that punishes dissent, shields insiders, and invites

extremism into governance.

A retired senior

judge, also speaking on condition of anonymity, offered this assessment:

“When courts become

tools of executive power, democracy collapses in disguise. The resignations of

top justices and the reshaping of the bench contradict Articles 94 and 116A

of the Constitution. Without judicial independence, the Constitution is just

ink on paper.”

As student

protestors once chanted for a “New Bangladesh,” what they have received is an

old pattern under a new face. The rule of law is not selectively applied

justice—it is, by definition, universal. Until the Yunus government

recognizes this truth, the cycle of repression will continue, and

Bangladesh’s dream of democracy will remain deferred.

✍️ Report Prepared By: Fozla Rabbi Robna